Scaling Authorized Content Access in microservice Architecture

Background

In 2020, Freeletics had huge surge in traffic as users started to look for best digital health app to keep them fit during the COVID-19 lockdown. This initially led to performance degradation of our servers, about which we were alerted from our monitoring services and user’s complain. We were in firefighting mode for almost 3 weeks, and after repetitive investigation and improvements, we brought back our system health status to green.

During the investigation, we found that one of the reasons for poor performance was the circular dependency between our services (microservice) and clients, when properly checking the authorization of user to access a paid content. In this blog, I will explain what were the immediate steps we took to tackle this issue, and what improvements we made in long term to make the payment authorization scalabale.

The term “coach access” would mean that the user has an active subscription to our paid content.

Old Process

We have created our microservices based on business domain. For an instance, a “Payment Service” is responsible for keeping the record of user’s subscription, renewal, upgrade, and cancellation, where as “Training Service” is responsible for keeping the record of user’s training plans and progress.

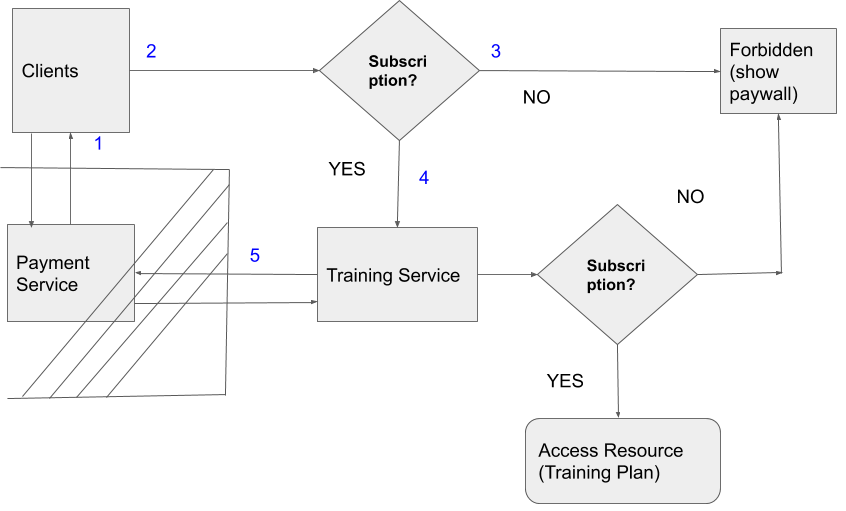

The old process to authorize the access to paid content was:

- Client makes a call to payment service to check if the user has an active coach (active subscription)

- If the user didn’t have an active subscription, the user was given limited access to the product

- If the user had active subscription, user could access paid content, like “Daily Training Plan”

- To fetch user’s current “Training Plan”, Client makes the request to the training service

- The training service, upon receiving the request, double checks with payment service, if the requesting user has an active coach

- If the user has active coach, training service returns the user’s training plan, else returns unauthorized/forbidden error.

Authorized Content Access

Authorized Content Access

In the figure above, we can see that request number 1 and request number 5 (the shaded area), creates a circular call to payment service. Both call checks if user has an active subscription, and one of the call can be made redundant.

Iteration 1 : Introduce Caching

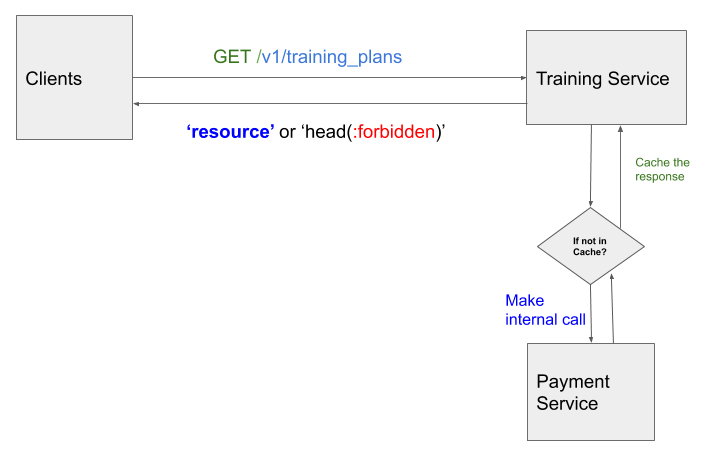

As an immediate step to tackle this during the firefight, we introduced caching user’s coach access status. To explain it, by referencing above two services, the training service would first check in its cache to see if the user has coach access. If there is a ‘cache-hit’, it would return the content to client. In case of ‘cache-miss’, it would make internal call to payment service to check if the user has a ‘coach access’. If the user has an active coach access, the state is cached, else it is not.

The training service will then continue to answer the client request with either the requested content or forbidden error, based on user’s coach access status.

Caching Coach Access

Caching Coach Access

This was the solution we came up with during the firefighting mode, and it worked well. The average duration for the endpoint with coach access was decreased along with the number of internal calls made to payment service. It was enough for us to get our health indicator back to green.

Since the status of user was cached until the end of day, if the user subscription was canceled, refunded, or blocked, the user would still have access to the paid content, instead of having it revoked immediately.

But, we could live with user having one extra coach subscription day for free.

Iteration 2: Event Driven Cache Invalidation

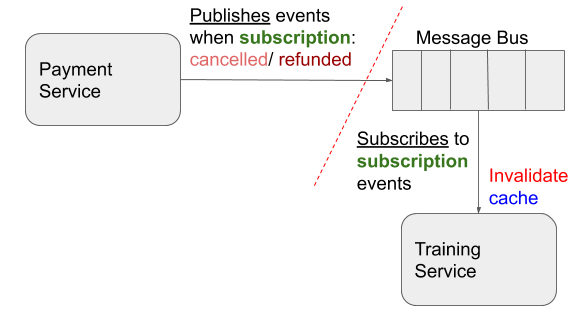

As the part of improvements and refactoring quick fixes made during the firefighting weeks, we revisited the above solution, and found a way to invalidate the cache.

Invalidating Cache

Invalidating Cache

The cache invalidation was based on pub/sub model. We already had message bus (Amazon SQS) and events (Amazon SNS) configured in our system between our services. As second iteration, services (e.g. Training service) interested in “payment events”, like ‘cancellation’ and ‘refund’ of a subscription, subscribed to those events. On receiving those events, the subscribed service would then invalidate the user’s coach access status from their cache.

This made the revoking of access to paid content upon blocking/cancellation of subscription, almost instantly (based on queue processing).

Iteration 3: Token Based Authorization

So far, the solution worked fine and it was capable to handle bigger traffic without performance degradation. However, this discovery of internal dependencies between microservices raised further questions:

- Are we building a microservice or distributed monolith (with internal dependencies between services)?

- What amount of data is okay to be replicated between services?

- For e.g., is it okay to duplicate the user subscription data from payment to training service?

- How about creating a “common database” that can be accessed by all services? Is it against the ethos of microservice?

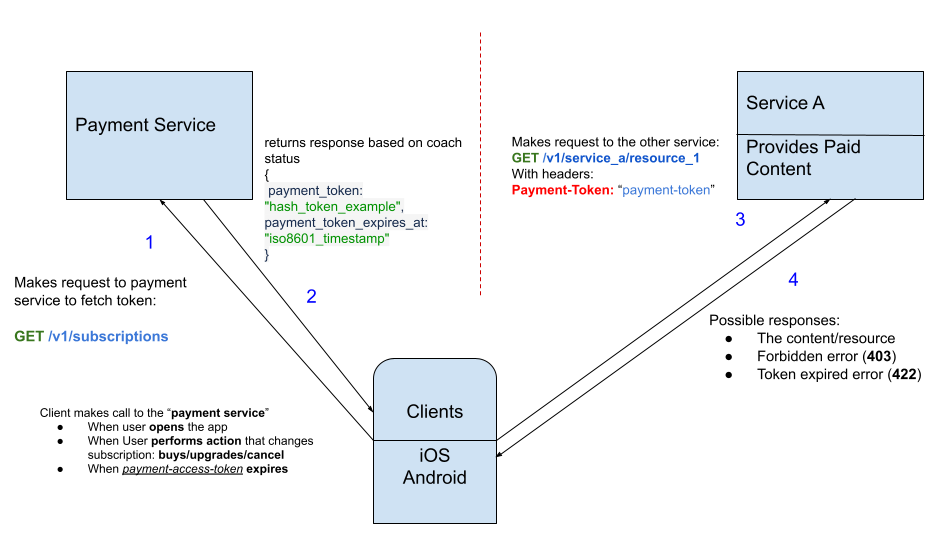

As the next phase of refactoring, we wanted to make payment service the only arbiter of payment authorization, and not make other services dependent upon the internal calls to it.

To achieve this in a simple way, we leveraged the usage of “token based authorization”.

Clients would make calls to different services based on the API contracts, and be able to fetch different resources correctly, by presenting valid authorization.

This would invert the flow control solely to client.

Token Based Content Authorization

Token Based Content Authorization

Now, when the client calls payment service to check if a “user” has an active subscription or not, they also get “payment-access-token”.

Client can then spend this “payment-access-token” to access other resources from other services. “Other services”, would check the validity of “payment-token”, and respond to the request to access paid resource with the “content” or an “error”.

The error is handled by client according to it’s type. If it is “token-expired”, request to fetch fresh token is done to payment service.

With this simple refactoring, we made the services agnostic of each other in regards of payment authorization. As the cherry on top, our new token based payment authorization made the request for content access faster than the previous cache based authorization, which made internal calls to payment service on ‘cache-miss’.

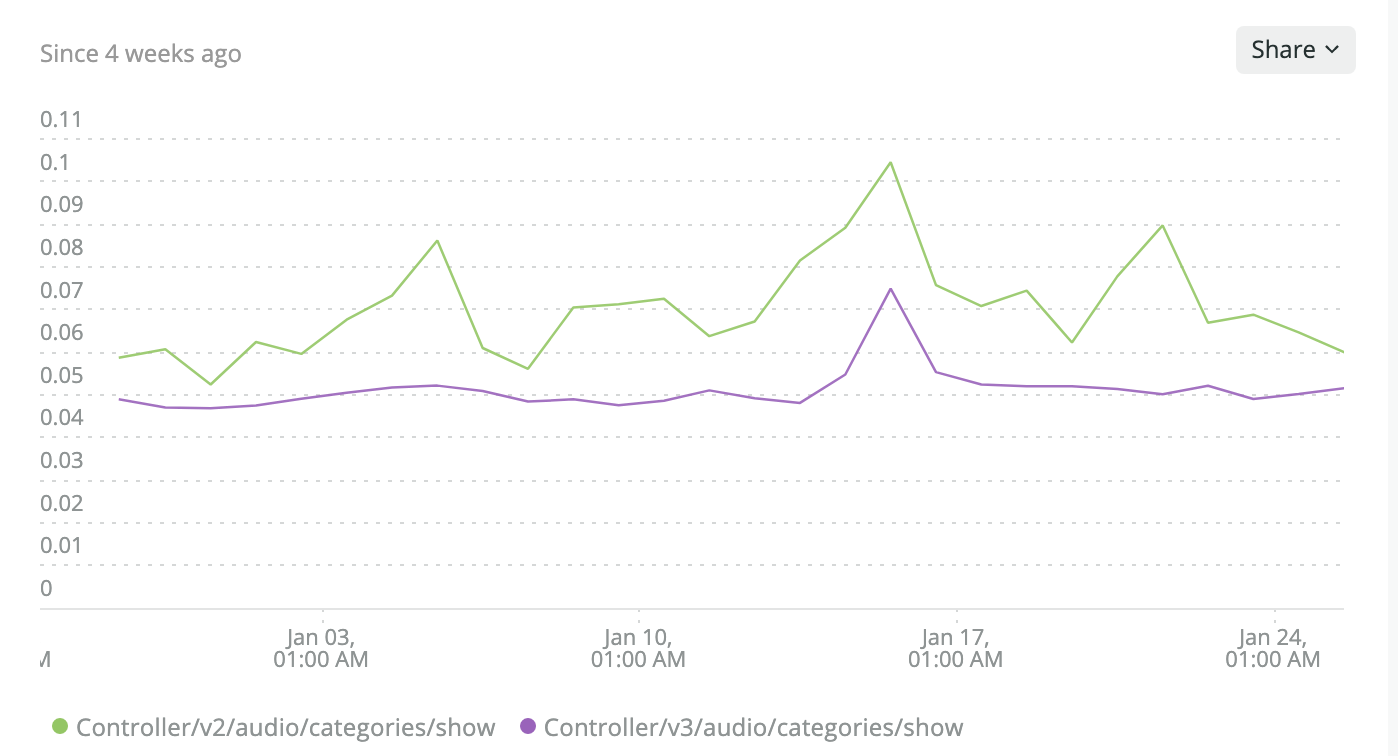

Average Response Time (v3: endpoint with refactoring, v2: older implementation)

Average Response Time (v3: endpoint with refactoring, v2: older implementation)

We ended up with bit cleaner architecture with loose coupling between services, and faster request response.

Conclusion

The refactoring started as a part of firefighting the degraded performance of our services, and ended up with completely new implementation of payment authorization. The first two iteration was purely Backend related, but for the third one, it required bigger collaboration across the academies (iOS, Android, QA). We started with discussion on the new API contracts, and listing out the services and endpoints that depended upon payment service for content authorization. We chose to start with the service with lower impact (blast radius) based on the number of hits per minute. When the prototype worked on the first service, we gradually started implementing the change on other services.

Some of the learning that we can take are:

- Take one step at a time, and work in iteration, based on the urgency

- Lookout for simple solutions (KISS principle)

- Sometime we can map existing solution from one problem domain, into another (existing token based ‘user authentication’, into ‘paid content authorization’)